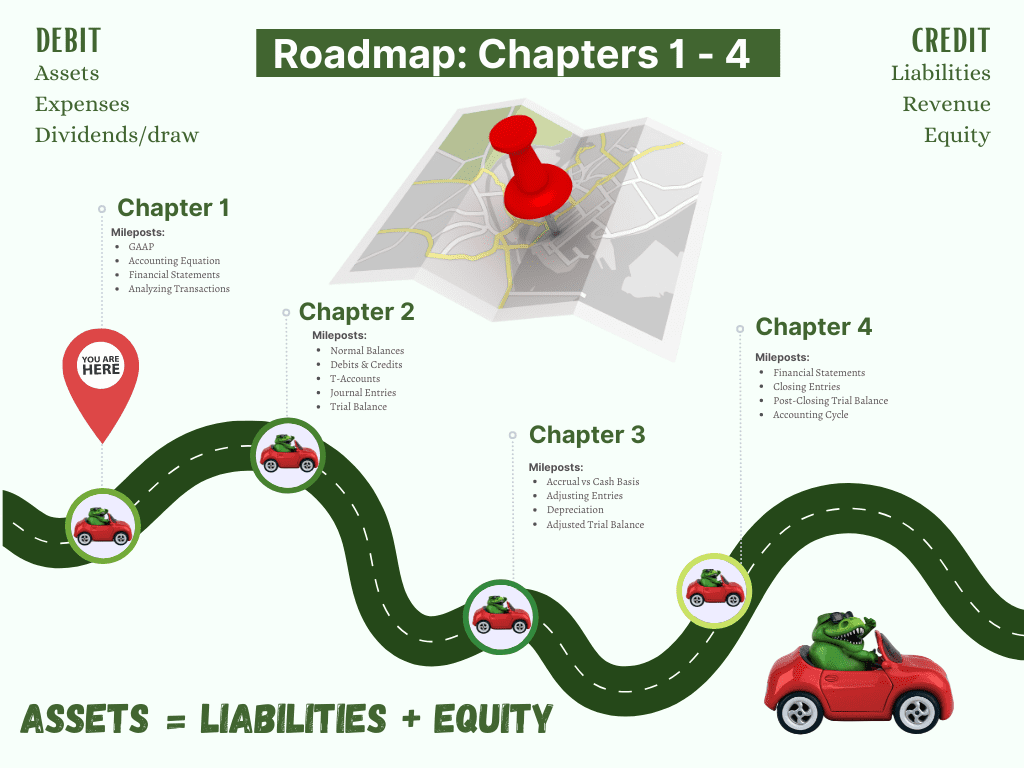

The first four chapters of Financial Accounting or Principles of Accounting I contain the foundation for all accounting chapters and classes to come. It’s critical for accounting students to get a good foundation in the first few chapters. We’ve developed this resource to help accounting students master the basics of analyzing accounting transactions.

To analyze accounting transactions follow these steps:

- Is this a business transaction or is it informational? For example, signing a rental agreement for office space, is informational. No change has happened in the financial records. Making a rent payment is a business transaction–a change has happened in the financial records. If a change has happened in the financial records, it’s a transaction that needs to be recorded.

- Reading through the transaction, see what accounts are being impacted. In the case of the rent payment, Rent Expense and Cash are the accounts being impacted. They are the accounts that are changing. If a sale to a customer has happened, a revenue account (Sales, Fees Earned, Rent Revenue) and an asset (either Accounts Receivable or Cash) is being impacted.

- Determine what types of accounts the impacted accounts are. For example, Rent Expense is an Expense, Cash is an Asset, Sales is a Revenue account, Accounts Receivable is an Asset.

- Determine whether the impacted accounts are increasing or decreasing. An expense increases, a revenue increases, cash or accounts receivable are increasing or decreasing.

- Based on whether the impacted account is increasing or decreasing, apply the rules of Normal Balances and debit and credit. For example, if an asset like cash is increasing, cash is an asset, assets have a normal debit balance, accounts with a normal debit balance increase on the debit side. A revenue account has a normal credit balance, an account with a normal credit balance increases on the credit side.

- Determine the amount being debited and credited.

You helped me better understand chapters 1-4 which helped me get an A on my midterm. Now on to test #3 and using your videos as a continued resource. Please keep sharing. You’re a great teacher! Thank you!

Lisa A, Youtube Subscriber

Accounting Basics

Before you can understand how to analyze transactions, you’ll need to have a good understanding of the foundation of Accounting. If you need to better understand the Accounting Equation, Normal Balances, and Debits and Credits. Check out this article: How to Know What to Debit and What to Credit in Accounting. It will take you step by step through understanding how accounting works.

Accounting Transactions Step by Step

Every accounting textbook for your first accounting class, uses very similar transactions. We’ll take actual transactions from various textbooks and break each transaction down using the steps for analyzing transactions.

In Chapter 1 of most textbooks, the Accounting Equation is introduced. The exercises in the chapter take the transactions and use the Accounting Equation to track those transactions in a spreadsheet format. If you need a refresher on the Accounting Equation, watch this video:

In Chapter 2, students are introduced to T-Accounts and journal entries. Similar transactions are used to show how to track changes in the Accounting Equation using first T-Accounts and then journal entries.

Accounting Basics–Building a Strong Foundation

In this article, we’ll walk through step by step how to analyze example transactions using the three different approaches used in accounting textbooks. But first, let’s make sure we have the basics down so we can build a strong foundation.

What is a Chart of Accounts?

Each business has its own group of accounts, called a Chart of Accounts. The accounts in the Chart of the Accounts are the accounts we use to categorize transactions.

Before we start to analyze transactions for a business, we need to know what the accounts are that a business is tracking. Each business can give a slightly different name to its accounts.

One business might call its Cash account “Checking” or “Bank Name Checking”. Another business may have multiple bank accounts to track.

Each business also has specific information it needs to track. A manufacturing business would need to track Raw Materials Inventory. A merchandising business would need to track Merchandise Inventory. Each business has its own group of accounts, called a Chart of Accounts. The accounts in the Chart of the Accounts are the accounts we use to categorize transactions.

For a refresher on Chart of Accounts, watch this video:

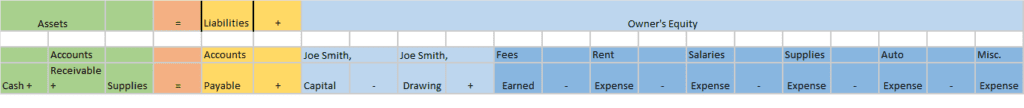

Example Company Chart of Accounts

Here is the Chart of Accounts we’ll be using for the example company as we analyze and enter our transactions. This chart includes the Account Type and the Normal Balance to aid in determining how to increase and decrease accounts.

| Chart of Accounts | Account Type | Normal Balance |

| Cash | Asset | Debit |

| Accounts Receivable | Asset | Debit |

| Supplies | Asset | Debit |

| Accounts Payable | Liability | Credit |

| Joe Smith, Capital | Equity | Credit |

| Joe Smith, Drawing | Equity | Debit |

| Fees Earned | Revenue | Credit |

| Rent Expense | Expense | Debit |

| Salaries Expense | Expense | Debit |

| Supplies Expense | Expense | Debit |

| Auto Expense | Expense | Debit |

| Miscellaneous Expense | Expense | Debit |

Examples of Accounting Transactions

The examples of accounting transactions we are using are very similar to what you’ll find in your accounting textbook, homework, and quizzes. In this article, we’ll walk through step by step how to analyze theses transactions using the three different approaches used in accounting textbooks.

Here are the accounting transactions we’ll use to demonstrate the three methods for analyzing and recording transactions. We’ll use the same transactions for each of the methods.

| On June 1 of the current year, Joe Smith established a business to manage rental property. He completed the following transactions during June: |

| 1. Opened a business bank account with a deposit of $55,000 from personal funds. |

| 2. Purchased office supplies on account, $3,300. |

| 3. Received cash from fees earned for managing rental property, $18,300. |

| 4. Paid rent on office and equipment for the month, $8,300. |

| 5. Paid creditors on account, $2,290. |

| 6. Billed customers for fees earned for managing rental property, $30,800. |

| 7. Paid automobile expenses for the month, $1,380, and miscellaneous expenses, $1,800. |

| 8. Paid office salaries, $7,300. |

| 9. Determined that the cost of supplies on hand was $1,250; therefore, the cost of supplies used was $2,050. |

| 10. Withdrew cash for personal use, $13,800. |

Analyzing Accounting Transactions

Accounting textbooks take three different approaches to teaching students how to analyze transactions. The purpose of showing three different methods is to first introduce the concept of how the Accounting Equation is impacted by transactions.

Once students grasp that concept of how transactions impact the Accounting Equation, we introduce T-Accounts so students can see what happens in the individual accounts in a visual format.

Then, we move to journal entries where students use the rules of debit and credit to increase and decrease accounts.

This article will walk through each of the methods using the same example transaction for each method so you can see that each method has the same result. The three methods are:

- Expanded Accounting Equation (most textbooks introduce this method in Chapter 1)

- T-Accounts (most textbooks introduce this method in Chapter 2)

- Journal Entries (most textbooks introduce this method in Chapter 2, this will be the method used moving forward)

For an overview of Analyzing Transactions, watch this video:

Free Spreadsheet Showing Examples, Problems, and Answers

The spreadsheet that accompanies this article shows examples of typical accounting transactions with homework problems and answers. It can be downloaded free here:

Method 1: Transaction Analysis Using the Accounting Equation

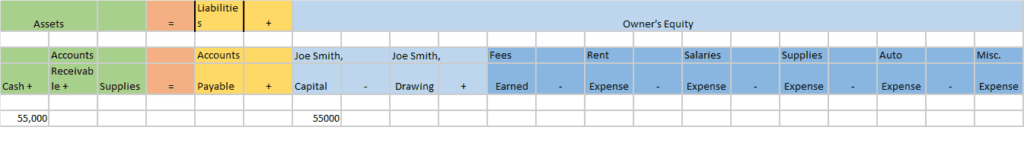

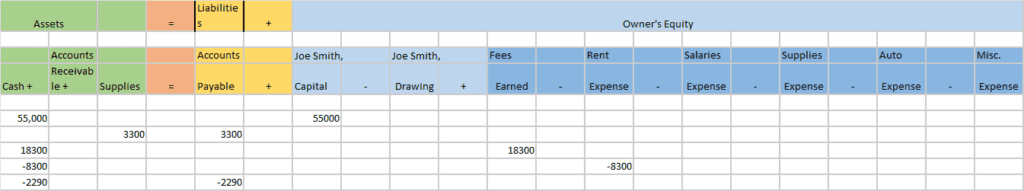

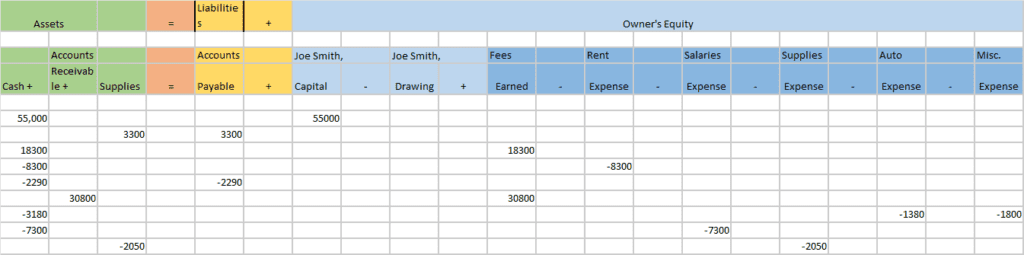

In Chapter 1 of most textbooks, a spreadsheet of the Accounting Equation is used. Here’s an example of that spreadsheet:

We’ll take each sample transaction and work through the solution for each using the Accounting Equation spreadsheet.

Transaction 1. Opened a business bank account with a deposit of $55,000 from personal funds.

With this transaction, we first determine what is happening. In this case, the owner has started a new business, opened a business checking account, and deposited $55,000 of his own money.

We aren’t concerned with Joe Smith’s personal accounting. We only care about the accounting for his business.

Next, determine what accounts are changing. The business is getting cash. Cash is an Asset. In the spreadsheet, we enter $55,000 in the Cash column.

What else is happening with this transaction? Joe Smith will now have Equity in the business because of his investment of $55,000. In the spreadsheet, we enter $55,000 in Joe Smith, Capital on the same line as the Cash part of the transaction.

The Accounting Equation is in balance, meaning the left side equals the right side. $55,000 = $55,000.

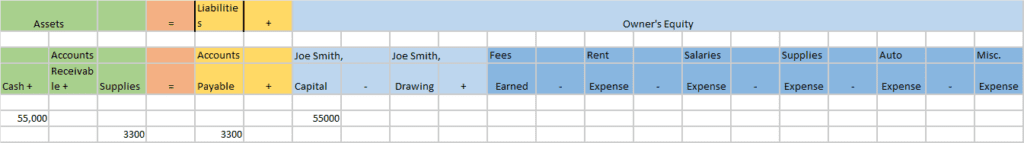

Transaction 2. Purchased office supplies on account, $3,300.

Note: Accounting textbooks use two different accounts with the word “Supplies” in the account name–Supplies and Supplies Expense. Supplies is an Asset. Supplies Expense is an Expense. Some textbooks have started using “Supplies Asset” to distinguish between the two.

Supplies (the Asset) acts like an Inventory account. We purchase an inventory of Supplies that we will use up over a period of time. Supplies Expense is for recording the “using up” of the Supplies (asset).

Confusing? Yup! Let’s work through it.

Whenever you see this transaction in your textbook, assume it is the asset, not the expense.

In this transaction we are getting Supplies. In the Asset section of the spreadsheet we enter $3,300. Whenever you purchase something the other side of the transaction will always be either Cash or Accounts Receivable. We’re either paying for it now (like at the cash register of the office supply store) or we’re paying for it later when the company sends us a bill.

In accounting textbook language “on account” always means money has not yet changed hands. We are going to pay this later. That means its Accounts Payable. We enter $3,300 in the Accounts Payable column.

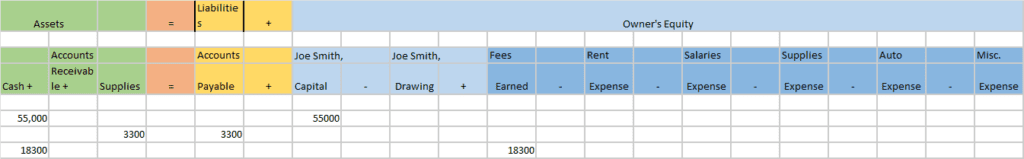

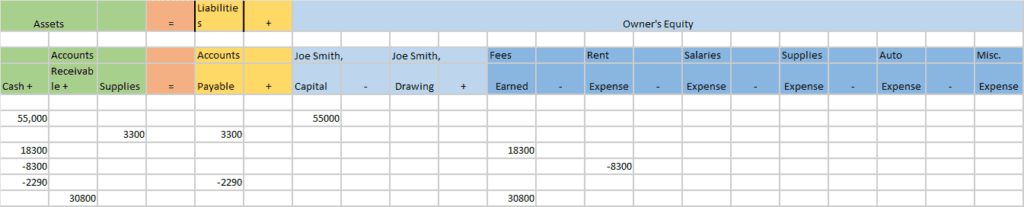

Transaction 3. Received cash from fees earned for managing rental property, $18,300.

This company is in the business of managing rental property. The fees it receives are revenue. According to the Chart of Accounts, the name of our Revenue account is Fees Earned. Our revenue is increasing so we will put $18,300 in our Fees Earned column.

When we are selling to our customers in a transaction, the customers are either paying us now or they are paying us later. If the transaction says “on account“, it means no money has changed hands. This means its Accounts Receivable. The customer will pay later. If a transactions says “received cash,” that means they paid you now. In our Cash column, we enter $18,300.

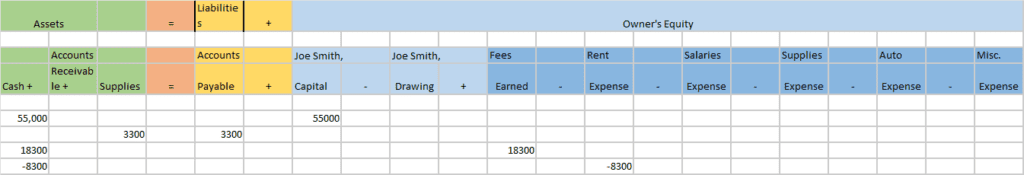

Transaction 4. Paid rent on office and equipment for the month, $8,300.

What are we paying? We are paying rent. What happens to our Cash account when we pay bills? It decreases. We enter a -$8,300 in the Cash column. Our Chart of Accounts has a Rent Expense account for us to record rent. We enter -$8,300 in the Rent Expense column.

Why is Rent Expense a negative number? Because Expenses decrease Equity. In this spreadsheet format, we are using the Expanded Accounting Equation. Revenue increases Equity and Expenses decrease Equity.

(This might feel confusing. It’s okay. Just remember to put a minus sign in front of any Expenses you enter.)

Transaction 5. Paid creditors on account, $2,290.

This transaction needs some background information. Creditors are businesses or people you owe money to. In our business, when we purchase something and plan to pay for it later, it gets recorded in Accounts Payable. At some point in the future, we will pay that bill. We will pay our creditors.

Because this is a new business and we only have four transactions before this one, it’s easy to determine what creditor we are paying. We are paying for the office supplies we purchased “on account” in Transaction 2. We have a bill in our Accounts Payable for $3,300. We are paying $2,290 of that bill which will leave a balance of $1,010 in Accounts Payable which we will pay at a different time.

Because we are paying a bill, our Cash is going to decrease. We enter -$2,290 in the Cash column. Our Accounts Payable is decreasing (we owe less than we did before). We enter -$2,290 in the Accounts Payable column.

Transaction 6. Billed customers for fees earned for managing rental property, $30,800.

When a transaction says “billed”, it means you are creating an invoice to send to your customer. Your customer hasn’t paid you yet. This means we are increasing Accounts Receivable by $30,800. We also now have revenue. Our revenue account is called Fees Earned. We increase Fees Earned by $30,800.

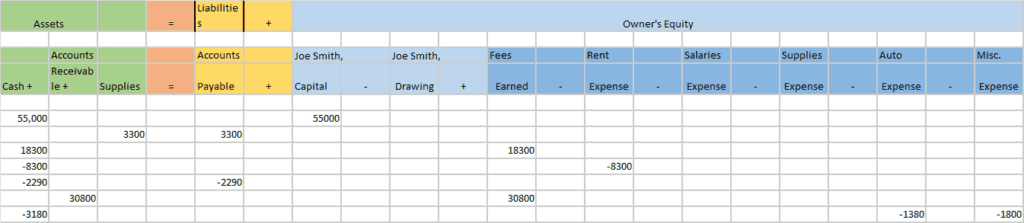

Transaction 7. Paid automobile expenses for the month, $1,380, and miscellaneous expenses, $1,800.

Oh, this is a cool one! When you reach the point of doing these transactions as Journal Entries, rather than as a spreadsheet, this transaction would be done as a “compound journal entry.” Rather than having two parts to the transaction, this one has three parts. Three accounts are being impacted by this transaction.

The first account being impacted is Cash. We are paying out a total of $1,380 + $1,800 = $3,180. Our Cash is decreasing so we enter -$3,180 in the Cash column.

Now, what are we paying? We are paying Automobile Expenses of $1,380. Record that as -$1,380 in the Automobile Expense column. And we are paying Miscellaneous Expense of $1,800. Record that as -$1,800 in the Miscellaneous Expense column. [Remember, expenses decrease equity. That’s why, in this format, we use a minus sign.]

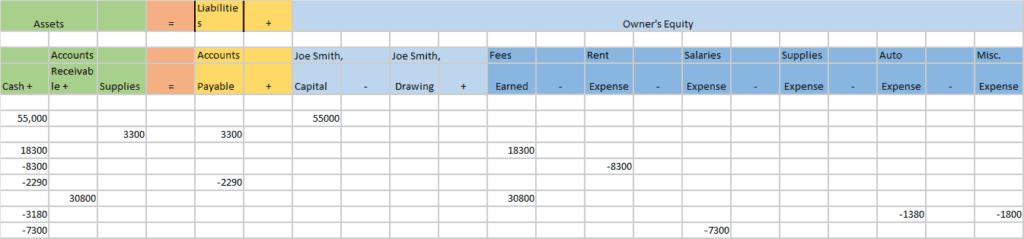

Transaction 8. Paid office salaries, $7,300.

It’s time to pay those hardworking employees who keep the business running. The accounts being impacted are Cash (it’s decreasing) and Salaries Expense (it’s increasing). Let’s pop that into the spreadsheet.

Transaction 9. Determined that the cost of supplies on hand was $1,250; therefore, the cost of supplies used was $2,050.

Aha! Here’s that tricky part with the Supplies (asset) and Supplies Expense transaction. Textbook authors love to throw this one in. (For more about textbook authors and their trickster ways, watch this video.)

What we’re about to do is actually a Chapter 3 adjusting entry. Here’s what’s going on.

Back in Transaction 2, we purchased $3,300 of office supplies. We said this was like an Inventory of Supplies. We’re putting all those supplies in an office supply closet. Then, as we take office supplies out of the supply closet, the inventory value drops. At the end of the month, we need to determine how much we actually used for office supplies during that time.

We have three numbers here:

- What we started with

- What we used

- What we have left

We know we purchased $3,300 of supplies. That’s our starting amount. The wording of this transaction can be different depending on the textbook. In our example transaction, its spelled out pretty clearly. “Supplies on hand” means what we have left, $1,250. “Cost of supplies used” means what we took out of our inventory for that month.

Right now, our Supplies (asset) balance says we have $3,300 of supplies. But we don’t. We only have $1,250. That means we need to “adjust” our balance to the actual amount. How do we do that?

We’re going to reduce Supplies (asset) by the difference between what we started with and what we ended up with. $3,300 (beginning) – $1,250 (ending) = $2,050 (what we used). When you use up an asset, it becomes an expense. We’ll use the Supplies Expense account to track that.

Here’s what that looks like:

When we update the balance in that column, we now have $3,300 – $2,050 = $1,250 (the true balance of the Supplies (asset) account. Just remember that the balance of the Supplies (asset) account after the adjustment should be the actual amount of inventory still in the supply closet.

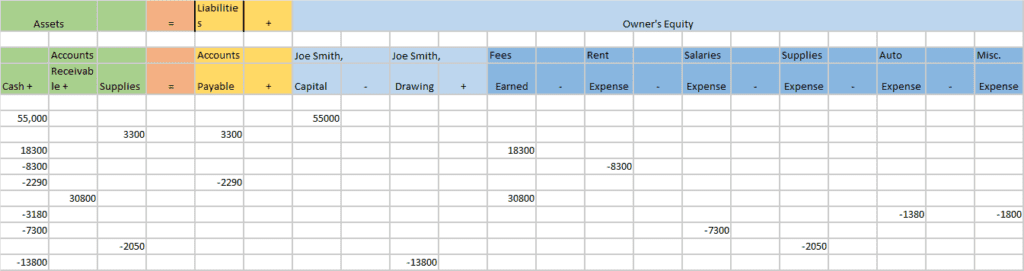

Transaction 10. Withdrew cash for personal use, $13,800.

When an owner puts money into a business (as this owner did in the first transaction), we increase their equity in the business. When an owner takes money out of the business we decrease their equity. Because we want to keep track of withdrawals separately for business and tax purposes, we use a separate account called Owner’s Withdrawals or Owner’s Draw or Dividends.

In this transaction, the owner is withdrawing cash so we know that Cash decreases. The other side of the transaction is a reduction in equity for which we’ll use our separate account for owner’s draw. Here’s what that looks like:

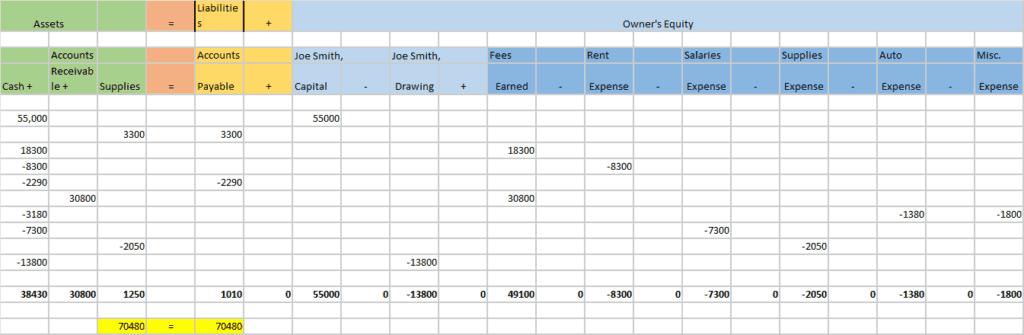

Once we’ve entered all the transactions into the spreadsheet, it’s time to total the columns and do a check to see if our Accounting Equation is still in balance. Check to make sure each transaction is on its own line. Check to see if each transaction is in balance (each line should have the same amount on either side of the transaction. (Don’t forget, this spreadsheet is available for you to download and practice on your own!)

And there you have it! Analyzing Transactions using the Accounting Equation transaction spreadsheet handled!

If you’d like to walk through this step by step in video format, watch this video:

In the second part of this article, we move into Chapter 2 and learn how to analyze accounting transactions using T-Accounts and Journal Entries. You can find that article here:

-

How to Know What to Debit and What to Credit in Accounting

If you’re not used to speaking the language of accounting, understanding debits and credits can seem confusing at first. In this article, we will walk through step-by-step all the building

-

How to Analyze Accounting Transactions, Part One

The first four chapters of Financial Accounting or Principles of Accounting I contain the foundation for all accounting chapters and classes to come. It’s critical for accounting students to get

-

What is an Asset?

An Asset is a resource owned by a business. A resource may be a physical item such as cash, inventory, or a vehicle. Or a resource may be an intangible

-

What are Closing Entries in Accounting? | Accounting Student Guide

What is a Closing Entry? A closing entry is a journal entry made at the end of an accounting period to reset the balances of temporary accounts to zero and

-

What is a Liability?

A Liability is a financial obligation by a person or business to pay for goods or services at a later date than the date of purchase. An example of a

-

What is Revenue?

Revenue is the income generated by a business in the normal course of operations. It represents the sale of goods and services to customers or clients. For a non-profit organization,