If you’re not used to speaking the language of accounting, understanding debits and credits can seem confusing at first. In this article, we will walk through step-by-step all the building blocks you need to debit and credit like a pro.

In accounting, Debit means the left side of an account and Credit means the right side of an account. We increase and decrease accounts by debiting them or crediting them. Knowing whether to debit or credit an account depends on the Type of Account and that account’s Normal Balance. An account’s Normal Balance is based on the Accounting Equation and where that account is in the equation.

The account types are Asset, Liability, Equity, Dividends, Revenue, Expense. To increase an Asset, Dividend, or Expense account, we debit. To decrease those accounts, we credit. To increase an Equity (Capital), Revenue, or Liability account, we credit. To decrease those accounts, we debit.

What is the Accounting Equation?

Before you can understand debits and credits, you’ll need a little background on the structure of accounting. It all starts with the Accounting Equation. The Accounting Equation is the foundation of double entry accounting. It categorizes accounts into different account types. Those account types determine how debits and credits will be used to increase and decrease accounts.

Let’s dig into the Accounting Equation so you have the start of a solid foundation!

Basic Accounting Equation:

Assets = Liabilities + Equity (also known as Capital)

The Accounting Equation looks at what a company owns and compares it to what a company owes. The difference between the two is called equity. Let’s use a delivery van for a florist shop as an example to explain.

The florist shop purchases a delivery van for use in delivering flowers to customers. The florist shop paid $20,000 for the van. It purchased the van for a cash down payment of $5,000 and took out a loan for $15,000.

The delivery van is an asset. It’s something the company owns that has value and will be used to make revenue for the business. The company has an Asset that cost $20,000.

Assets = $20,000 [Assets increased by the value of the delivery van we purchased.]

The company made a downpayment of $5,000 cash. Cash is also an Asset. It’s something the company owns that has value and will be used to make revenue for the business. Because the company paid out the cash, the asset value has decreased. We no longer have that $5,000 in the bank account.

Assets = $20,000 – $5,000 = $15,000 [Assets increased by the $20,000 delivery van and assets decreased by the amount of cash we spent.]

The company also took out a $15,000 loan to pay for the delivery van. That loan is a liability. A liability is an obligation to pay based on whatever terms were decided between the company and the lender.

Liabilities = $15,000 [Liabilities increased by $15,000, the amount of the loan for the delivery van.]

Coming back to the Accounting Equation, now we have:

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

$15,000 = $15,000 + 0

Equity is zero because for every dollar of assets we have, we have a dollar of liability. It’s the same as the bank giving you a 100% mortgage (liability) for a house purchase. You have no equity in the house, the bank essentially owns all of it until you start to make payments.

Asset (house) = Liability (mortgage) + Equity (zero)

Obviously, that’s not a great financial position to be in!

Back to our florist shop.

Let’s say the company had $50,000 in cash to start with and only used $5,000 for the purchase of the van. The Accounting Equation changes:

Assets = Cash ($50,000 – $5,000) + Delivery Van ($20,000) = Liability ($15,000) + Equity ($50,000)

Total Assets $65,000 = Liability $15,000 + Equity 50,000

The difference between Assets and Liabilities is Equity.

As transactions occur, the Accounting Equation changes. Accounts increase and decrease, and as that happens the Accounting Equation is continually changing. The Owner’s Equity is continually changing. Accounting is all about tracking those changes!

When we track the changes in the Accounting Equation, we use the three basic accounts (Assets, Liabilities, and Equity). But it wouldn’t make sense to just put all of our Assets in a big pile and dump all our Liabilities in a bucket. We need more detail than that.

We need to know of our Assets, how much is Cash, how much is Delivery Van, how much is Inventory. We need to know of our Liabilities, how much is the delivery van loan, how much is the mortgage. The Accounting Equation helps us do that by giving us a foundation we can build on.

You can learn more about how the Accounting Equation works by watching this video:

What are the 5 Account Types in Accounting

When we track transactions in Accounting, we use different buckets to keep track of what is owned, what is owed, and what the owner’s or shareholders’ Equity. Those buckets are called Account Types. The five account types (our buckets) that we use are:

- Assets

- Liabilities

- Equity

- Revenue

- Expenses

Each Account Type is used to track changes to specific parts of the Accounting Equation.

- Assets are used to track what the business owns. Some Asset examples are: Cash, Accounts Receivable, Inventory, Vehicles, Equipment, and Buildings

- Liabilities are used to track what the business owes. Some Liability examples are: Accounts Payable Notes Payable, Loans Payable, Mortgage Payable, Salaries Payable

- Equity accounts are used to track the changes in the owner’s or shareholders’ equity. Does a transaction make the owner’s equity more valuable or less valuable. Equity accounts are based on the legal form of the business (Sole Proprietor, Partnership, LLC, SCorp, Corporation). Examples of Equity accounts for a Sole Proprietor might be: John Smith, Capital and John Smith, Drawing (or John Smith Dividends). Equity accounts for a corporation might be: Shareholder’s Equity and Shareholder’s Dividends.

- Revenue accounts are used to track income that comes from selling to customers. For our florist shop, our revenue account might be Flower Sales or Retail Sales. The name of the revenue account(s) used will depend on the type of business. A business selling professional services like an accountant or a lawyer might use Professional Fees or Service Revenue. Businesses can have multiple revenue accounts to track revenue from different sources. Our florist shop might track Retail Sales and Wholesale Sales. Or Retail Sales and Online Sales.

- Expense accounts are used to track all the different expenses a business incurs to make revenue. Some examples of Expenses are: Telephone Expense, Wages Expense, Fuel Expense, Office Supplies Expense, Insurance Expense, Rent Expense. As with Revenue accounts, a business can have as many Expense accounts as needed to keep track of specific expenses. For example, if our florist has five delivery vans, the business might want to track repairs and maintenance for each van by assigning each a Repairs and Maintenance Expense account [Repairs and Maintenance Expense–2020 Delivery Van]. (This is correct accounting, but not recommended. There are better ways to do this using accounting software.]

Now that we have our five account types identified, it’s time to return to the Accounting Equation. We said the basic Accounting Equation is: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. We said Assets are what a business owns and liabilities are what a business owes. The difference between the two is Equity. Now let’s dig deeper into Equity. It is arguably the most important part of the equation.

When our florist decided to start their business, they put their own money into the business. That investment of money bought them equity in the business. They started with zero equity. The business didn’t exist. When they put money in the business, their equity increased. Just like with Assets and Liabilities, Equity increases and decreases based on activity in the business. When Equity increases, the owner has more value. When Equity decreases, the owner has less value.

Let’s look at how Equity can increase in a business. We already saw one way. The owner invested their own cash. An investment by the business owner increases the owner’s equity. Another way the business owner’s equity increases is through Revenue. When the business sells something to its customers, the owner’s equity increases. The owner has more value in the business.

To test that theory let’s use Amazon as an example. If Amazon’s sales go up does that create more value for Amazon’s shareholders? Of course! If Amazon’s sales go down does that create less value for Amazon’s shareholders. You bet! If our florist shop sells more to customers, the value of the owner’s equity increases.

Now let’s look at how Equity can decrease in a business. If our florist shop owner decides to take some of their invested funds back out of the business (called Owner’s Draw or Owner’s Withdrawal or Dividends), equity decreases. Equity also decreases when businesses have expenses. And all businesses have expenses! Every dollar spent to make revenue (buying flowers, paying employees, paying rent, paying insurance), reduces equity.

The relationship between Revenue and Expenses has a direct impact on the value the owner has in the business. It determines whether a business is operating at a profit or a loss. If a business is operating at a profit, the owner’s value increases. If a business is operating at a loss, the owner’s value increases.

To carry that one more step, we can now understand that:

Revenue – Expenses = Profit/Loss

If Revenue is higher than Expenses, the business has a profit and the owner’s equity increases.

If Expenses are higher than Revenue, the business has a loss and the owner’s equity decreases.

This brings us to the Expanded Accounting Equation.

Expanded Accounting Equation:

The Expanded Accounting Equation demonstrates the effect of the changes in Owner’s Equity because of owner investments (money the owner adds to the business), Dividends or Withdrawals (money the owner takes out of the business), Revenue (an increase in equity because of sales to customers), and Expenses (a decrease in equity due to expenses incurred in making Revenue)

Assets = Liabilities + Beginning Equity + (Investments – Dividends + Revenue – Expenses)

Essentially, Accounting is all about tracking the changes to the Owner’s Equity. Some equity comes from investments into the business by the owner. Some equity comes from having more Assets than Liabilities. Some Equity comes from Revenue. And then, reductions to Equity come from withdrawals and expenses.

What is the Purpose of Accounting?

Our job as accountants is informing the business owner how their business is doing. We do that by tracking changes and summarizing that information in reports called Financial Statements.

Business owners use Financial Statements to help them monitor and improve the health of their business over time. Each financial statement shows a different part of the picture of of the business, much like having x-rays from different angles to better understand an injured ankle. Each angle shows different information.

We use four basic Financial Statements to show different parts of the overall picture of the business’s health. Those Financial Statements are Income Statement, Statement of Owner’s Equity, Balance Sheet, and Statement of Cash Flows.

- Income Statement (also called Profit and Loss Statement or P&L) shows whether the business is making a profit. The formula for the Income Statement is Revenue – Expenses = Profit or Loss. As we said before, Profits increase Equity and Losses decrease Equity.

- Statement of Owner’s Equity (also called Statement of Shareholders’ or Stockholders’ Equity or Statement of Partners’ Equity or Statement of Members Equity) shows where the Owner’s Equity was at the beginning of the month or year and what changes happened to it during that period. Did the owner put money in or take money out, did the business have a profit or loss?

- Balance Sheet shows the breakdown of Assets, Liabilities, and Equity. It lists all of the Asset accounts (Cash, Accounts Receivable, Inventory, Vehicles, etc.). It lists all of the Liability accounts (Accounts Payable, Salaries Payable, Mortgage Payable, etc.). And it shows the summary of the Owner’s Equity.

- Statement of Cash Flows shows where the cash came from and where it went. How much cash came into the business? Was it cash from operating the business (for example, customers paying us) or did it come from investing (selling an asset) or financing activities (taking out a business loan). How much cash went out of the business? Was it cash we used to pay our employees and our suppliers? Or, was the cash used to make a loan payment or to purchase an asset? And most importantly, do we have more or less cash than we started with?

You can learn more about Financial Statements by watching this video:

How Accounting Works

Now that we have a good foundation of what the purpose of accounting is and what the structure of accounting is, we can dig into how accounting works. How do we track those changes to accounts so we can tell the business owner how the financial health of their business has changed since the last time we reported to them?

What are Normal Balances?

The first part of knowing what to debit and what to credit is knowing the Normal Balance of each type of account. The Normal Balance of an account is either a debit (left) or a credit (right). It’s the column we would expect to see the account balance show up. If an account has a Normal Debit Balance, we’d expect that balance to appear in the Debit (left) side of a column. If an account has a Normal Credit Balance, we’d expect that balance to appear in the Credit (right) side of a column.

Each account type (Assets, Liabilities, Equity, Revenue, Expenses) is assigned a Normal Balance based on where it falls in the Accounting Equation. We also assign a Normal Balance to the account for Owner’s Withdrawals or Dividends so we can track how much an owner has withdrawn from the business or how much has been paid to Stockholders for Dividends.

What are the Normal Balances of each type of account?

Each account type has a normal balance. That normal balance is what determines whether to debit or credit an account in an accounting transaction. Returning to the Expanded Accounting Equation:

Assets = Liabilities + Beginning Equity + (Investments – Dividends + Revenue – Expenses)

For the moment, let’s ignore the entire Equity section and just focus on Assets and Liabilities. Based on the rules of debit and credit (debit means left, credit means right), we can determine that Assets (on the left of the equation) have a Normal Debit Balance. Liabilities (on the right of the equation) have a Normal Credit Balance.

Let’s move to the Equity section. Equity is on the right side of the Accounting Equation. The right side is the credit side so Equity has a Normal Credit Balance.

If an account has a Normal Debit Balance, it increases on the debit side and decreases on the credit side.

If an account has a Normal Credit Balance, it increases on the credit side and decreases on the debit side.

As an example, we can return to the purchase of the florist’s delivery van.

The delivery van price was $20,000. The delivery van is an Asset. An Asset has a Normal Debit Balance. The Asset is increasing (we are adding the Asset to our accounts). To increase an Asset we Debit it.

We made a $5,000 cash down payment to purchase the van. Cash is an Asset. An Asset has a Normal Debit Balance. The Asset is decreasing (we have less cash than before). To decrease an Asset we Credit it.

We took out a loan to pay for the remainder of the purchase price of the delivery van. A loan is a Liability. A Liability has a Normal Credit Balance. The Liability is increasing (we owe more now than we did before we bought the van.) To increase a Liability we Credit it.

When we make a payment on the loan, the Liability is decreasing. A Liability has a Normal Credit Balance. To decrease a Liability we Debit it.

Now, let’s look at the Expanded Accounting Equation again:

Assets = Liabilities + Beginning Equity + (Investments – Dividends + Revenue – Expenses)

The rest of the accounts to the right of the Beginning Equity amount, are either going to increase or decrease owner’s equity.

We said:

- An Investment of cash by the owner increases Equity. Equity has a Normal Credit Balance. Equity increases on the Credit side.

- Paying out a Dividend or an Owner’s Withdrawal decreases Equity. Equity has a Normal Credit Balance. Equity decreases on the Debit side.

- Revenue increases Equity. Equity has a Normal Credit Balance. Equity increases on the Credit side.

- Expenses decrease Equity. Equity has a Normal Credit Balance. Equity decreases on the Debit side.

What is the Normal Balance for Owner’s Withdrawals or Dividends?

When we’re talking about Normal Balances for Dividends (Owner’s Withdrawals), we assign a Normal Balance based on the effect on Equity. Dividends decrease Equity. Equity has a Normal Credit Balance. We decrease Equity by a Debit. We want to specifically keep track of Dividends in a separate account so we assign it a Normal Debit Balance. The effect on Equity is to decrease it. Consider Dividends to be a sub-account of Equity.

What is the Normal Balance for Revenue Accounts?

When we’re talking about Normal Balances for Revenue accounts, we assign a Normal Balance based on the effect on Equity. Revenue increases Equity. Equity has a Normal Credit Balance. We increase Equity by a Credit. Because of the impact on Equity (it increases), we assign a Normal Credit Balance.

What is the Normal Balance for Expense Accounts?

When we’re talking about Normal Balances for Expense accounts, we assign a Normal Balance based on the effect on Equity. Expenses decrease Equity. Equity has a Normal Credit Balance. We decrease Equity by a Debit. Because of the impact on Equity (it decreases), we assign a Normal Debit Balance.

To further understand how Normal Balances relate to the effect on Equity, watch this video:

Which Accounts Have a Normal Debit Balance? Which Accounts Have a Normal Credit Balance?

Let’s recap which accounts have a Normal Debit Balance and which accounts have a Normal Credit Balance. Then, I’ll give you a couple of ways to remember which is which.

Normal Debit Balance:

Assets, Dividends (or Owner’s Withdrawals), Expenses

Increase by Debit, Decrease by Credit

Normal Credit Balance:

Liabilities, Capital (or Owner’s Equity), Revenue

Increase by Credit, Decrease by Debit

To reinforce your understanding of Normal Balances, watch this video:

Is There an Easy Way to Remember Normal Balances for Accounts?

After Eating Dinner, Let’s Read Ebooks

DEALER

| Debit | Credit | |

| Dividends | + | – |

| Expenses | + | – |

| Assets | + | – |

| Liabilities | – | + |

| Equity | – | + |

| Revenue | – | + |

What are Debits and Credits Used for in Accounting?

Think of debits and credits as pulling the levers to make changes in an account. If you debit an asset, you are telling your accounting system to increase it. If you credit an asset, you are telling your accounting system to decrease it.

Let’s use your checking account as an example. Let’s deposit some money into the account. That means the balance is increasing.

- What type of account is it? A bank account is an Asset.

- What is the Normal Balance of an Asset? An Asset has a Normal Debit Balance.

- Are we increasing the Asset or decreasing the Asset? We are increasing.

- How do you increase an Asset? By debiting it.

Now, let’s say we withdraw some cash from the account. The balance is decreasing.

- What type of account is it? A bank account is an Asset.

- What is the Normal Balance of an Asset? An Asset has a Normal Debit Balance.

- Are we increasing the Asset or decreasing the Asset? We are decreasing.

- How do you decrease an Asset? By crediting it.

To reinforce your understanding of Debits and Credits, watch this video:

What is Double Entry Accounting?

But we aren’t just increasing or decreasing the Asset. There’s another side to this transaction. We also want to know where the money we deposited came from and where the money we withdrew went to. This is called double entry accounting. It allows us to collect information about the transactions that happen in a business.

Let’s say the deposit we made is from the sale of some products in our business. We want to track that sale. We do this using a Revenue account, let’s call our Revenue account Product Sales. When you sell a product, your Revenue increases.

- What type of account is it? A Revenue account.

- What is the Normal Balance of a Revenue account? A Revenue account has a Normal Credit balance.

- Are we increasing the Revenue or decreasing the Revenue? We are increasing.

- How do you increase a Revenue? By crediting it.

Now, let’s say the money we withdrew from our checking account was to purchase some office supplies for the business. Office Supplies is an expense for the business.

- What type of account is it? An Expense account.

- What is the Normal Balance of an Expense account? An Expense account has a Normal Debit balance.

- Are we increasing the Expense or decreasing the Expense? We are increasing our Expense.

- How do you increase an Expense? By debiting it.

How Do You Do Journal Entries in Accounting?

Journal Entries are where we do our debiting and crediting. A journal entry is a set format that accountants use to record what accounts are being increased and decreased. Here’s the format of a journal entry:

| Debit | Credit | ||

| Date | Account Name | ||

| Account Name | |||

| Description |

What is a Chart of Accounts?

A Chart of Accounts is a listing of the accounts a company uses to categorize transactions. The accounts are the buckets of information a business needs to track. A Chart of Accounts is specific to the individual business and what is important for that business to track. A Chart of Accounts lists accounts of the same type together for organizing and simplicity.

When doing a journal entry (or using T-accounts), the Account Name represents an account in the Chart of Accounts. The exact name of the account should always be used in the journal entry. For example, if the account name in the Chart of Accounts is Telephone Expense, the account name in the journal entry should be Telephone Expense, not Phone Expense or Telephone or Cell Phone. The account name must always match the Chart of Account name. This prevents confusion.

Let’s bring our transactions together in our journal format.

We made a deposit in our checking account. We’re going to name our Cash account “Checking”. The money came from Product Sales. We’ll say it was $1,000. We are increasing our Asset account called Cash and increasing our Revenue account called “Product Sales.”

| Debit | Credit | ||

| Jan 1, xx | Checking | 1000 | |

| Product Sales | 1000 | ||

| Sold product to customers |

By debiting our asset, we have increased it. By crediting our revenue, we have increased it. (If that feels confusing, refer back to the Rules of Debit and Credit.)

Let’s say we also paid $50 cash for office supplies. We are decreasing our Asset called Checking and we are increasing our Expense called Office Supplies Expense.

| Debit | Credit | ||

| Date | Office Supplies Expense | 50 | |

| Checking | 50 | ||

| Purchased office supplies |

By debiting our expense, we have increased it. By crediting our asset we have decreased it.

For more information about how journal entries work in accounting, watch this video:

What Happens After the Journal Entry?

Once a journal entry is done, we then record that to the individual accounts being effected by the transaction. This is called “posting to the accounts.” Line by line, the journal entries are entered in the individual accounts, debits are recorded as debits and credits are recorded as credits.

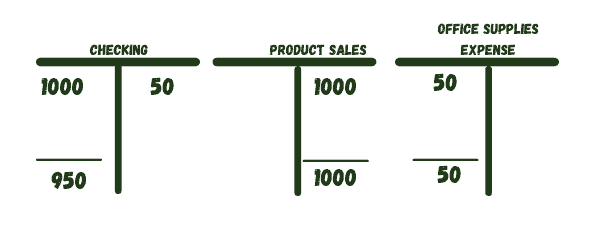

We can use either T-accounts or Ledgers to record the journal entries.

What is the Difference Between a T-Account and a Ledger?

A T-account is simplified visual look at the activity of of different accounts. It’s called a T-Account because it is shaped like a T. The left side is the debit side, the right side is the credit side. A T-Account does not show a running balance in an account. Instead, each account is “tallied up” at the end of the accounting period. T-Accounts are used in the classroom to teach accounting students how to post. They are also used by accountants to sketch out more complex transactions before completing a journal entry.

A ledger is the usual method for posting journal entries to accounts. It contains columns for debits and credits, and also provides columns to keep balances updated. (You wouldn’t want to wait until the end of a month before you find out if you have any cash in your Checking account!)

For more information on the difference between T-Accounts, Journals, and Ledgers, watch this video:

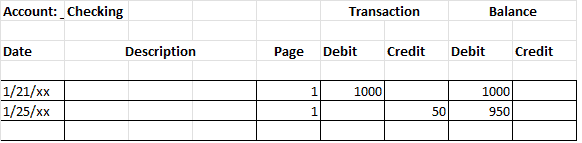

Here’s an example of a Ledger:

When we take our example transactions from above and post them to the accounts, we can see the effect of the debits and credits.

Let’s look at what happened to the balances of these three accounts after our journal entries:

When the journal entries we completed are posted to the accounts, this caused changes in the account balances. That’s the journal entries’ entire reason for existing—making changes in accounts.

For additional examples on using T-Accounts, watch this video:

How to Analyze Transactions

For each accounting transaction, you can walk through the process of understanding the transaction, determining which accounts are impacted, what the account types are, and apply the rules of debit and credit. In accounting class, the same entries are used over and over making it easy to practice.

Let’s breakdown the step by step approach to determining what to debit and what to credit.

Debits and Credits Step by Step

- For each transaction, determine what accounts are impacted. (Example: Cash and Product Sales)

- For each account, determine if the account is increasing or decreasing. (Example: Cash is increasing and Product Sales is increasing.)

- What type of accounts are these? (Example: Cash is an Asset. Product Sales is a Revenue.)

- What is the Normal Balance for those accounts? (Assets have Normal Debit balance and Revenue has Normal Credit balance)

- To increase the Asset called Cash, debit it. To increase the Revenue called Product Sales, credit it.

- Record the journal entry using the journal entry structure.

- Post to the T-Accounts or Ledgers.

For practice doing typical accounting transactions, check out this video:

Some Good News!

For everyday accounting transactions, there are only a few that repeat over and over. You buy something, you sell something. Once you learn the basic journal entries, you’ll use them over and over again. That means it gets easier once you learn it the first time. Remember, accounting is a skill. The more you practice, the easier it becomes. Just think of it as building your accounting muscles!

-

How Do Journal Entries Work in Accounting?

Journal entries are one of the most fundamental and essential concepts in accounting. A journal entry is a record of a transaction that affects a company’s financial statements. Journal entries

-

What is a Statement of Shareholders’ Equity?

The Statement of Shareholders’ Equity is one of the four major financial statements. The function of the Statement of Shareholders’ Equity is to show changes in the value of equity

-

Accounting for Notes Receivable | Accounting Student Guide

What is a Note Receivable? A note receivable is formal payment agreement between two or more people or entities. It is a promissory note that specifies: Who the note is

-

How to Post Journal Entries to the Ledger

When a Journal Entry is made to record a transaction, that Journal Entry is then entered (posted) in the accounts being impacted. For example, when rent is paid, in the

-

What is the Accounting Equation?

Before you can understand debits and credits, you’ll need a little background on the structure of accounting. It all starts with the Accounting Equation. The Accounting Equation is the foundation

-

What is Owner’s Draw (Owner’s Withdrawal) in Accounting?

Owner’s Draw or Owner’s Withdrawal is an account used to track when funds are taken out of the business by the business owner for personal use. Business owners may use