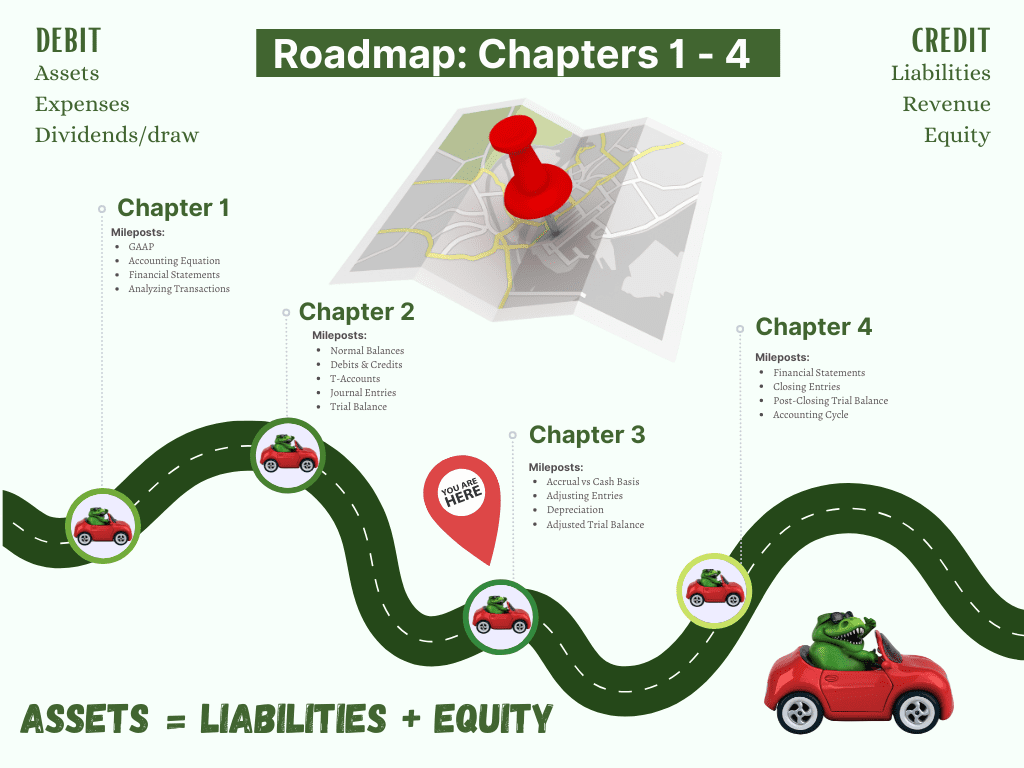

When all the regular day-to-day transactions of an accounting period are completed, the next step is to check on the balances of certain accounts to see if those balances need to be updated or changed using a type of journal entry called an Adjusting Entry.

What is an Adjusting Entry?

The purpose of an adjusting entry is to update revenue and expense accounts at the end of each accounting period (month or year) to conform to the rules of accrual basis accounting. Accrual basis accounting requires that revenues and their associated costs be recorded in the same accounting period. For example, if a store sells merchandise in June, the cost of purchasing that merchandise should also be recorded in June.

Why are Adjusting Journal Entries Necessary?

Under Accrual Basis Accounting, Adjusting Entries are necessary to ensure revenues and expenses are being recorded in the correct month or year. In Accrual Basis accounting, timing is everything. Revenue earned in June should be recorded in June, regardless of when cash is received. Expenses that match with that revenue should also be recorded in June, regardless of when the goods or services were received or paid for.

What is the Difference Between Cash Basis and Accrual Basis Accounting?

Under Cash Basis of accounting, revenue is considered to be earned when money is received. Expenses are considered to be incurred when those expenses are paid. Under Accrual Basis of accounting, revenue is considered to be earned at the time the work is done or goods are delivered, regardless of when cash changes hands. Expenses are considered to be incurred when goods are purchased or services delivered, regardless of when cash changes hands.

Under Accrual Basis accounting, we use accounts like Accounts Receivable and Accounts Payable to record transactions that have occurred (revenue earned or expenses incurred) where no cash has yet changed hands.

For a deeper understanding of Cash Basis and Accrual Basis in accounting, watch this video:

What is Revenue Recognition in Accounting?

The Revenue Recognition principle is part of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). The principle determines how and when revenue is “recognized.” In other words, it determines how and when a company puts revenue on its income statement. Under accrual basis accounting, revenue is considered earned when goods or services are delivered, regardless of when cash is received.

What is Expense Recognition in Accounting?

The Expense Recognition principle is part of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). This is also known as the Matching Principle. The principle states that expenses should be recognized in the same month as the revenue associated with that expense. For example, if a retail business sells goods to a customer in June, the cost of purchasing that merchandise should also be in June. The merchandise may have been purchased months before it sold. Accrual basis accounting is used to bring together the revenue and the related expenses in the same month.

To learn more about Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), watch this video:

What is the Adjusting Process?

At the end of each accounting period, adjusting journal entries are completed to update revenue and expenses accounts to accurately reflect changes to the accounts that have not been captured as part of day-to-day transactions. The adjusting process compares the current balance in an account to what the balance should be. An adjusting journal entry is completed to adjust the balance. Adjusting Entries are completed after all regular transactions are completed and before financial statements are created.

For example, a business has a delivery van for which $200 of depreciation expense is recorded each month. This is not captured in the day-to-day accounting transactions. It is done as an adjusting entry once a month to capture the expense.

For more in depth knowledge about Adjusting Entries, watch this video:

What Accounts Need Adjusting Entries?

Every Adjusting Entry includes one balance sheet account (Asset or Liability) and one income statement account (Revenue or Expense). Typical accounts that need adjusting are:

- Prepaid asset accounts (Prepaid Insurance, Prepaid Rent, Prepaid Expenses)

- Unearned liability accounts (Unearned Revenue, Unearned Rent, Customer Deposits)

- Payable liability accounts (Salaries Payable, Interest Payable, Sales Tax Payable)

- Contra Asset accounts (Accumulated Depreciation, Allowance for Doubtful Accounts)

- Revenue and Expense accounts related to the accounts listed above (Insurance Expense pairs with Prepaid Insurance, Depreciation Expense pairs with Accumulated Depreciation)

Which Accounts Do Not Need Adjusting Entries?

Generally, the accounts that do not need adjusting entries are:

- Cash accounts–the transactions in cash accounts are recorded throughout the month and do not need adjusting

- Land–Land is recorded at purchase cost and the value remains the same on the books until it is sold. (Land does not get depreciated so it doesn’t need a depreciation adjusting entry.)

- Equity accounts–equity is recorded as transactions happen: stock sales, owner’s investments, owner’s withdrawals, dividends.

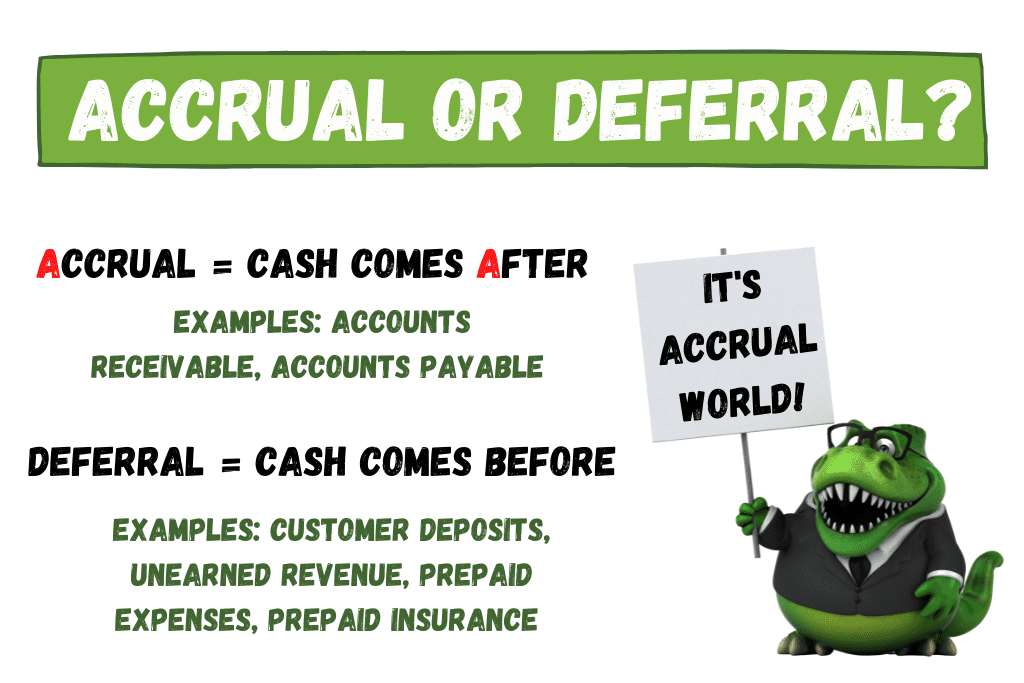

What is the Difference Between Accruals and Deferrals in Adjusting Entries?

The purpose of adjusting entries is to bring revenues and the associated expenses into the same accounting periods. The transaction types used to do this are called accruals and deferrals.

- Some transactions are paid after the revenue is earned (Accounts Receivable) or after the expense is incurred (Accounts Payable). These transactions are Accruals (cash comes after).

- Some transactions are paid in advance of the revenue (Unearned Revenue, Customer Deposits) being earned or the expense being incurred (Prepaid Insurance). These transactions are Deferrals (cash comes before).

Adjusting Entries are the accounting tool used to bring transactions into the correct accounting period.

What is an Accrual?

The purpose of Accruals is to allow the recording of revenues earned but no cash received (Accounts Receivable) and the recording of expenses incurred but no cash paid out (Accounts Payable). Accruals record revenue in the month earned and expenses in the month incurred, regardless of payment status. Accruals mean the cash comes after the earning of the revenue or the incurring of the expense.

For example:

- A company sells goods to a customer in June on account. The revenue belongs in the month of June, but the payment won’t be received until July. The cash comes after the point where the revenue is earned.

- A company purchases goods from a vendor in June on account. The expense belongs in the month of June, but the payment won’t be made until July. The cash comes after the point were the expense is incurred.

What is a Deferral?

The purpose of Deferrals is to allow the recording of prepayments of Revenues and Expenses. Deferrals record a liability for cash received before the revenue is earned. When the revenue is earned, the liability is decreased. Deferrals record an asset for cash paid before the expense is incurred. When the expense is incurred, the asset is reduced. Deferrals mean the cash comes before the earning of the revenue or the incurring of the expense.

For example:

- A company receives a deposit from a customer in May for work that will be done in June. The revenue belongs in the month of June, but the payment was received in May. The cash comes before the point where the revenue is earned.

- A company pays for a full year of insurance premiums on January 1. One-twelfth of the expense belongs in each month of the year, but the payment was made in January. The cash comes before the point were the expense is incurred.

Accounting textbooks generally divide adjusting entries into Accrual and Deferral categories. In this article, we separate adjusting entries into Revenue transactions and Expense transactions. This allows for a look at the contrast between Accruals and Deferrals within those Revenue and Expense transactions.

Adjusting Entries for Revenue

Adjusting entries involving Revenue accounts are divided into two categories, Accruals and Deferrals, based on when cash changes hands.

Adjusting Entries for Revenue Accruals

A Revenue Accrual occurs when revenue is earned, but cash has not been received (cash comes after). Whenever goods or services are sold to a customer on account, we have a Revenue Accrual:

| Accounts Receivable | 1000 | |

| Revenue | 1000 |

For transactions that occur as part of day-to-day operations, no adjusting journal entry is needed. The point where an adjusting entry becomes necessary is when Revenue is earned, but the customer has not been billed yet.

Let’s use a lawyer as an example. If a lawyer is working on a case that lasts months or years, they may not bill the customer until the case is settled. But work done each month on that case is earned revenue. A revenue accrual is done to enter the revenue into the month it was earned.

In accounting class, we use this entry to record revenue earned but not yet billed to the customer:

| Accounts Receivable | 1000 | |

| Revenue | 1000 |

In real life, this entry doesn’t work well since it makes the balance in Accounts Receivable for that customer look as though the customer currently owes the money. Instead of using Accounts Receivable, we can use an account called Unbilled Revenue. This is an asset account. It has a normal debit balance. It increases on the debit side and decreases on the credit side.

| Unbilled Revenue | 1000 | |

| Revenue | 1000 |

When the case is settled and the customer is billed, we move the amount out of Unbilled Revenue and into Accounts Receivable:

| Accounts Receivable | 1000 | |

| Unbilled Revenue | 1000 |

An adjusting entry to record a Revenue Accrual will always include a debit to an asset account and a credit to a revenue account.

Adjusting Entries for Revenue Deferrals

A revenue deferral occurs when a company is paid for goods or services in advance of the goods or services being delivered. (Cash comes before.) When cash is received, we increase cash and increase a liability. That liability account might be called Unearned Revenue, Unearned Rent, or Customer Deposit. It’s a liability because if we don’t do the work or deliver the goods, we need to give the cash back to the customer. Once we’ve done the work, we’ve earned the revenue. Until then, it’s a liability owed to the customer.

The original journal entry at the time the cash is received is:

| Cash | 1000 | |

| Unearned Revenue/Unearned Rent/Customer Deposit | 1000 |

The point where an adjusting journal entry is needed occurs when the work is completed (or a portion is completed.) Let’s look at some examples:

A customer makes a $2,000 downpayment on a custom furniture piece to be made by a cabinetmaker. The cabinetmaker’s original entry is:

| Cash | 1000 | |

| Customer Deposit | 1000 |

When the cabinetmaker finishes the work, they will do the following adjusting journal entry to move the amount from the liability account, Customer Deposit, to the Revenue account, Sales Revenue.

| Customer Deposit | 1000 | |

| Sales Revenue | 1000 |

The revenue is now earned and will appear on the Income Statement. The liability to the customer is now satisfied and is removed from the Balance Sheet.

A landlord requires prepayment of three months’ rent before a tenant can move into an office building. Rent is $2,000 per month. The original journal entry is:

| Cash | 6000 | |

| Unearned Rent | 6000 |

Each month that passes means the landlord earns one month of rent. An adjusting journal entry is done each month to move one month’s rent from the liability account, Unearned Rent, to the revenue account, Rent Revenue:

| Unearned Rent | 2000 | |

| Rent Revenue | 2000 |

Once the third month has passed, the balance in Unearned Rent will be zero. The liability has been reduced and removed from the Balance Sheet and the Rent Revenue has been recorded in the appropriate month.

An adjusting entry to record a Revenue Deferral will always include a debit to a liability account and a credit to a revenue account.

For more knowledge about Adjusting Entries for Revenue transactions, watch this video:

Adjusting Entries for Expenses

Adjusting entries involving Expense accounts are divided into to categories, Accruals and Deferrals, based on when cash changes hands.

Adjusting Entries for Expense Accruals

An Expense Accrual occurs when expenses are incurred, but cash has not yet been paid (cash comes after). Whenever goods or services are purchased by a company on account, we have an Expense Accrual:

| Consulting Expense | 1000 | |

| Accounts Payable | 1000 |

For transactions that occur as part of day-to-day operations, no adjusting journal entry is needed. The point where an adjusting entry becomes necessary is when an Expense is incurred, but the company has not been billed yet.

Let’s say a company hires a consultant for a big project. The work the consultant does in the month of June is an expense incurred in June. The consultant doesn’t bill the company until August for that work. The expense is still a June expense so we need to record that expense in the month where it belongs.

In accounting class, we use this entry to record expenses incurred but not yet billed by the vendor:

| Consulting Expense | 1000 | |

| Accounts Payable | 1000 |

In real life, this entry doesn’t work well since it makes the balance in Accounts Payable for that vendor look as though the company currently owes the money. Instead of using Accounts Payable, we can use an account called something like Unbilled Expenses or Unbilled Costs. This is a liability account. It has a normal credit balance. It increases on the credit side and decreases on the debit side.

| Consulting Expense | 1000 | |

| Unbilled Expenses | 1000 |

When the bill is received from the vendor, we move the amount out of Unbilled Revenue and into Accounts Payable:

| Unbilled Expenses | 1000 | |

| Accounts Payable | 1000 |

Adjusting Entries for Payroll Accruals (Salaries or Wages Payable)

Because our accounting textbooks always try to trip students up with adjusting journal entries for payroll accruals, let’s walk through the specifics of those transactions. Here’s an example of a transaction:

On June 30, wages due to employees but not paid are $1,200. Wages will be paid on July 8.

Here’s what’s going on with this transaction. We have a payroll that spans two accounting periods, June and July. The wages were earned by the employees in June. For the company, this means an expense was incurred in June and needs to be recorded in June. The actual cash will not be paid until July. (Cash comes after.) In the month of June, we record the expense and use a liability to track what is owed to the employees.

| Wages Expense | 1200 | |

| Wages Payable | 1200 |

In July, when the paychecks are produced for those wages, we move the amount out of Wages Payable and decrease cash using a journal entry:

| Wages Payable | 1200 | |

| Cash | 1200 |

Here’s where the tricky accounting textbook part comes in.

Because we have a payroll that crosses accounting periods, the paychecks we create for July 8 may contain wages earned in June and July. Our adjusting entry at the end of June recorded the Wages Expense for June, but not for July. Let’s say Wages for that period of time in July were $800. The total payroll amount for the payroll on July 8 is $1,200 + $800 = $2,000.

At this point, only $1,200 in Wages Expense is recorded. The Wages Expense occurring in July still needs to be recorded, and the total amount of $2,000 paid out to employees.

Here’s what our journal entry needs to be for July 8:

| Wages Expense | 800 | |

| Wages Payable | 1200 | |

| Cash | 2000 |

Wages Expense for June is $1,200. Wages Expense for July is $800. Total Cash out is $2,000. Wages Payable served as the account to cross over from one accounting period to the next.

An adjusting entry to record a Expense Accrual will always include a debit to an expense account and a credit to a liability account.

Adjusting Entries for Expense Deferrals

An expense deferral occurs when a company pays for goods or services in advance of the goods or services being delivered. (Cash comes before.) When a prepayment is made, we increase a Prepaid Asset and decrease cash. That Prepaid Asset account might be called Prepaid Expenses, Prepaid Rent, Prepaid Insurance, or some other Prepaid account. It’s an asset because if company does not receive the benefit of what it has paid for, it would receive cash back (for example an insurance policy refund).

In the case of a pre-payment of an insurance premium, the original journal entry at the time the cash is paid is:

| Prepaid Insurance | 1200 | |

| Cash | 1200 |

As each month passes, one month’s worth of insurance cost is moved from Prepaid Insurance to Insurance Expense. (As an asset is “used up”, it becomes an expense.)

| Insurance Expense | 100 | |

| Prepaid Insurance | 100 |

The same entry will be recorded once a month for twelve months until all the expense is captured in the correct month and the asset is fully “used up”.

An adjusting entry to record a Expense Deferral will always include a debit to an expense account and a credit to an asset account.

For more knowledge about Adjusting Entries for Expense transactions, watch this video:

Adjusting Entries for Depreciation

When a company owns Fixed Assets (for example, vehicles, equipment, or buildings), over time those assets lose value. That loss of value is called Depreciation. Because of the Matching Principle (expense recognition), that loss of value is tracked recorded throughout the life of the asset. This is done as an adjusting journal entry each month (or as a yearly adjusting entry–not the preferred method). The expense account used to record depreciation is Depreciation Expense. The historical cost of the asset is always preserved so the depreciation on an asset is tracked using a separate account called Accumulated Depreciation. Accumulated Depreciation is a contra-asset. It has a normal credit balance. It is increased on the credit side and decreased on the debit side.

The adjusting entry to record depreciation of a Fixed Asset is:

| Depreciation Expense | 100 | |

| Accumulated Depreciation | 100 |

For a deeper understanding of Depreciation, watch this video:

To understand how Depreciation is calculated, watch this play list:

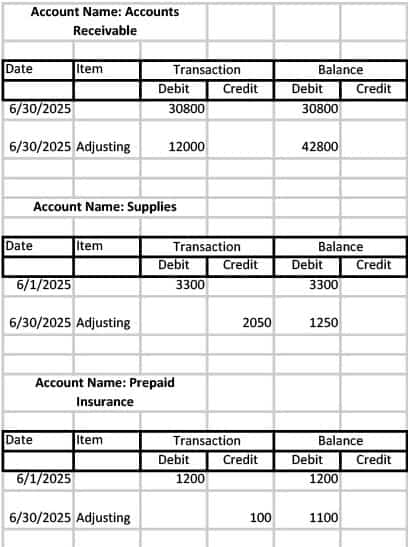

How to Post Adjusting Entries to Accounts

When adjusting journal entries are completed, each entry is posted to the individual accounts, just as regular journal entries are. The one difference is that in the Item column, the word “Adjusting” is entered to signify that this is an adjusting entry. This allows for easy identification if a transaction needs to be checked for accuracy. Here is an example of what the accounts looks like once adjusting entries have been posted:

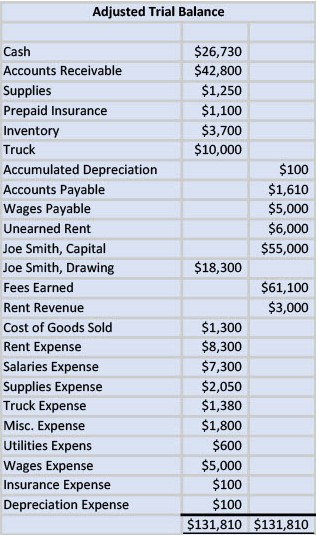

How to Prepare an Adjusted Trial Balance

Once adjusting journal entries are posted to accounts and the balances are updated, the next step is to complete an adjusting trial balance. The adjusted trial balance is simply a listing of all accounts and their balances after adjusting entries are completed. Debit balances are listed in the left (debit) column. Credit balances are listed in the right (credit) column. The balances of each column should be equal. This is the final check point before preparing financial statements.

Here is a sample Adjusted Trial Balance:

For more information about the Adjusted Trial Balance, watch this video:

Preparing Financial Statements from the Adjusted Trial Balance

Once the Adjusted Trial Balance is finished, the next step in the accounting process is to prepare Financial Statements.

For an introduction to Financial Statements, watch this video:

-

Difference Between Depreciation, Depletion, Amortization

In this article we break down the differences between Depreciation, Amortization, and Depletion, discuss how each one is used, and what the journal entries are to record each. The main

-

Adjusting Journal Entries | Accounting Student Guide

When all the regular day-to-day transactions of an accounting period are completed, the next step is to check on the balances of certain accounts to see if those balances need

-

What is a Contra Account?

A contra account is an account used to offset the balance in a related account. When the main account is netted against the contra account, the contra account reduces the

-

How to Calculate Straight Line Depreciation

Straight-line Depreciation is used to depreciate Fixed Assets in equal amounts over the life of the asset. The basic formula to calculate Straight-line Depreciation is: (Cost – Salvage Value) /

-

How to Calculate Declining Balance Depreciation

Declining Balance Depreciation is an accelerated cost recovery (expensing) of an asset that expenses higher amounts at the start of an assets life and declining amounts as the class life

-

How to Calculate Units of Activity or Units of Production Depreciation

Units of Activity or Units of Production depreciation method is calculated using units of use for an asset. Those units may be based on mileage, hours, or output specific to